Monsters and Manuals is back with a post about the quixotic quest for ‘realism’ in fantasy adventure games. Noisms makes the point that even convincing works of fantasy fiction are set in worlds that are only as ‘realistic’ as necessary for the suspension of disbelief. I think this is an important thing to consider when engaging in world building for fantasy gaming, but I think that a distinction must also be drawn between the veneers of 'historical credibility/accuracy' that work for fiction, and the veneers that work for a game, particularly a fantasy adventure game such as D&D.

A work of fiction can get by with very rare monsters, just one site of adventure, or even just one adventure - because the whole thing is a massive railroad. I've tried playing Lord of the Rings like a Fighting Fantasy gamebook, but I still haven’t got the bit where I can make a decision. A fantasy world made for fiction can have a more convincing veneer of ‘realism’ because most of the world can be filled with the mundane. Adventure doesn’t need to be everywhere, it doesn’t need to be in lots of places, it just needs to be in the one place the characters go.

A work of fiction can get by with very rare monsters, just one site of adventure, or even just one adventure - because the whole thing is a massive railroad. I've tried playing Lord of the Rings like a Fighting Fantasy gamebook, but I still haven’t got the bit where I can make a decision. A fantasy world made for fiction can have a more convincing veneer of ‘realism’ because most of the world can be filled with the mundane. Adventure doesn’t need to be everywhere, it doesn’t need to be in lots of places, it just needs to be in the one place the characters go.

They've taken the railroad to Isengard! To Isengard! To Isengard!

A game such as D&D needs adventure to be everywhere. It needs to be in enough places that the exercise of player character ‘freedom’ does not depend on quantum dungeons appearing wherever the players go, or years of in-game mundanity while the player characters traverse the world without coming across the Lair of the Spider Queen, or the Crypts of the Last Men, or… These travels might involve peril, even opportunities for interesting roleplay, but not for fantasy adventure.

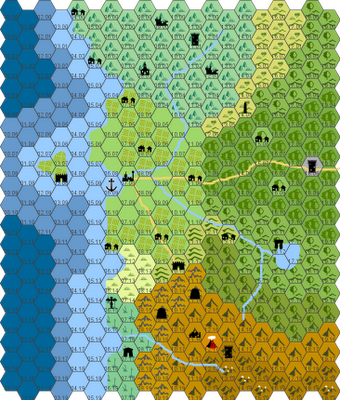

In the end we are back to my post on Titan – and I promise to switch to another topic soon; we’ve been playing using the elegant mechanics of Lamentations of the Flame Princess, but with the tone of the game taken from D&D read through Titan – which in summary, even if you don’t like adventurers as ‘rock stars’, is that a world for fantasy adventure needs to be a world packed with fantasy adventure. If accurately representing medieval demographics, economics, politics etc. gets in the way of this, then these have to be done away with. OR, the inconsistencies have to be glossed over – this is the cost of playing a fantasy adventure game in a pseudo-historical setting.

.jpg)