"What does your Character want to do?"

"How should I know?"

Giving PCs 'world knowledge' [*1] is a central problem of a sandbox campaign. Sure, the Character part of 'Player Character' knows, in principle, a lot about the world, but that doesn’t, in itself, much help the Player. If we’re running a tightly plotted 'railroad', the GM can tell the Player what the Character knows, as appropriate. What is appropriate is determined by the plot, and perhaps moderated by a skill/characteristic check. But what is 'appropriate' world knowledge if you are trying to build Player (and Character) agency into the game at a more fundamental level?

(An aside - I'm aware that I'm teaching fish to swim, here, for most people who read this.)

Well, a Player will never reach the level of world knowledge that we have about our own, real, world, which allows us to act freely, to make any number of decisions of where to go and what to do, given adequate resources. We are not constrained by our lack of world knowledge, but by our family ties, employment obligations, duties, social norms, and our limited resources. PCs in a sandbox campaign are not only constrained by these factors, but also by the fact that the Player making decisions on their behalf hasn’t spent 20/30/40-odd or more years being socialised into the geographical, political, social, and mythic possibilities of the incomplete, fictional world in which their Character adventures.

What are the sources of world knowledge for Players? Well, obviously, a GM might provide a description of the setting as a handout. The D&D Gazetteers actually did this quite well, with a players' section that described what characters might know of the history, myth, politics and social structure of the region. Something similar for a DIY setting need not be so detailed [*2] – it is the player’s job to ask questions. The players can put meat on the skeleton that the GM provides, either by prompting on-the-fly-world creation or by engaging in collaborative world creation themselves.

"What is the most important local festival?"

"I don’t know – didn’t Locnar the Brave grow up here? You tell me."

Of course, this needs inventive players who have bought into the concept. And the GM always has the privileges of elaboration – to flesh out the one line concept in ways that might surprise the player – and, of course, veto.

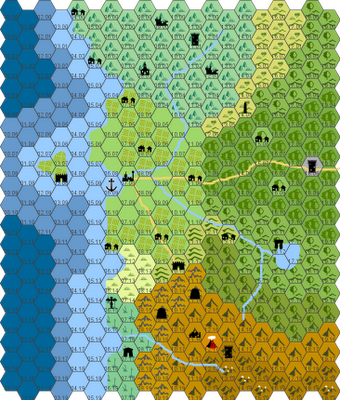

A much more evocative source of world knowledge are maps (

a good post on the subject of maps can be found on the Hill Cantons blog). A staple of fantasy fiction a map covered in place names and geographical features should excite any adventurer. The map doesn't need to be accurate, or to scale, or of an area much greater (at the start) than of Threshold and the surrounding few miles. A hex map might allow exploration to be mechanised somewhat, but a more abstract map might serve our purposes – of giving PCs the possibilities to act – just as well.

And then we get to rumour tables (

there's a nice rumnour table here at Blue Boxer Rebellion). The world should hum with the chatter of rumour tables. They don't necessarily need to be random – though we might enjoy letting the dice decide, and there are various ways of doing this, some of which (especially in skill based games or games that use characteristic checks) can reward roleplaying – but NPCs (even generalised as 'the people in town are talking about') provide ways to populate the developing fantasy world with possibilities for adventure. A more structured way of providing adventure appropriate world knowledge is the use of patrons – but the Players should have been provided with enough information about the possibilities of patrons for their Characters that the GM doesn’t need to turn every night in the pub into a speed-dating session for out-of-work strongarms and potential sugar daddies. With enough world knowledge, of the right kind, the Players should be able to seek out patrons, and their choices ought to be so unconstrained that their decisions force the GM to create patrons on the fly to meet the actions of the players. Fewer notices pinned to trees in the centre of Nuln, more PCs creating the world-on-the-fly, even if they don’t know it, by thinking up original ways to get paid to kill monsters (or whatever).

But two bog standard standard features of a D&D-style game are really exciting me about building both the world and Player world knowledge – random encounters and randomly rolled treasure. An encounter in itself is pretty adventurous, and there is no reason why it should be so simple as, 'You run into some bandits. Fight!'

Daddy Grognard has been developing

'An Adventure for Every Monster'. So far he’s up to Cockatrice, so there a lot more monsters to come. My thinking at the moment is that there is no reason that random encounters couldn’t perform an even greater world building role by incorporating MORE random tables. Tables of adventure seeds and geographic features would create three points of variation providing interesting (and potentially very strange) perpectives that can be quickly fleshed out by GM improvisation on the structure of bare bones.

You can build a whole lot of stuff from bare bones.

You can build a whole lot of stuff from bare bones.

And last, treasure, the point of much of this adventuring, can itself provide a great in-game source of world knowledge. Lots of adventures do this in reverse – the PCs are tasked with recovering the Sceptre of Dismay from the cannibal bandits of the Jagged Hills. More often than not, that involves the GM telling the PCs what to do. Doing it the other way round, the PCs find a sceptre after exploring the Jagged Hills marked on their maps, investigating a rumour that they heard several sessions. The PCs acted, the GM filled in the world. And while the GM has an idea of what the sceptre is (and this should be fixed, lest it become a quantum sceptre), what the PCs decide to do with the sceptre that they found will both flesh out its ‘reality’ and its future – shaping the game world at both a meta-level (what exists in the world and how are these ‘things’ related) and at the level of its fictional history (what happens in the fictional world once the existence of these things are decided). Again, Daddy Grognard has been filling his Adventures of Every Monster with interesting treasures, and has started a complementary series, '

A Horde for Every Treasure Type'. Wow. But he’s not the only one, we have the

WFRP Random Treasure Generator, of course, and we have RuneQuest/OpenQuest found 'Found Items'

HERE and

HERE. Honestly, the latter link, to the list of Found Items at the Chaos Project, makes my own list seem paltry. 342 entries! But, hey, this game is building a world from the ground up, so here is a d10 table of shoes!

1 A pair of indigo dancing shoes in immaculate condition, in an elegant, plain wooden box.

2 A barrel of foul smelling vinegar, in which float 13 pairs of leather shoes.

3 A pair of knee-high riding boots. Etched into the hard leather is a dragon, with small red crystals for eyes, that coils up the wearer's thighs.

4 Three pairs of wooden clogs; small, medium, and large.

5 A pair of armoured boots with a nasty barbed spike on each toe-cap.

6 A rough sack filled with dirty children’s shoes. There are 20 pairs and 6 odd shoes.

7 A pair of fine shoes, suitable for a gentleman, with a hidden compartment in each heel. One heel contains a ‘lucky’ gold coin of an obscure design. The other contains a small green silk pouch containing white powder that acts as a stimulant.

8 A pair of glass slippers to fit very small feet. One of the slippers is chipped and is crusted with old blood.

9 A pair of sandals. The hairy feet of the previous owner are still inside them, cut off at the ankle.

10 A pair of waders made from seal skin that smell of the rancid oils used to waterproof them.

*1 'World knowledge' isn't about Players knowing the facts of the world, but knowing their Character's 'possibilities for action'.

*2 Although there is no reason why this handout need not be an ever growing document, providing short pen sketches of significant NPCs, organisations, and locations. The Players cannot be expected to retain the world knowledge of their Characters between sessions, so a well organised handout that develops into a guidebook (easily enough managed now we’re not building worlds in school exercise books but on endlessly editable electronic documents) might be one of the best ways of externalising the world knowledge of the characters without relying on the GM re-cap/prompt that might restrict PC agency.

Wholly derivative, but then I’m not trying to be original, I’m trying to build a world in which the players can’t help but point their characters towards adventure. But then I read a post by noisms, which has the effect of pointing out that my map, using a nominal scale of 5/6 mile across a hex, might well be at a hopelessly large scale – at least to be used as an adventureful hexcrawler in a world of foot travel over moors and through woods. And then, to rub it in, I find this article, at the Hydra’s Grotto, which points out that the whole of Skyrim would fit inside a single hex at this scale!

Wholly derivative, but then I’m not trying to be original, I’m trying to build a world in which the players can’t help but point their characters towards adventure. But then I read a post by noisms, which has the effect of pointing out that my map, using a nominal scale of 5/6 mile across a hex, might well be at a hopelessly large scale – at least to be used as an adventureful hexcrawler in a world of foot travel over moors and through woods. And then, to rub it in, I find this article, at the Hydra’s Grotto, which points out that the whole of Skyrim would fit inside a single hex at this scale!

.jpg)