Every now and then I write up session reports for the games

that I run. Often, weeks pass and they end up unwritten, lost like tears in the

rain. This is particularly the case when I run one shots, or short adventure

sequences.

Humph.

However, over the past couple of weeks we've been playing

some more Advanced Fighting Fantasy 2e – the game which occupied several months

of our gaming time as the party recovered the Crown of Kings [final play report here]. These games will

make AFF2e it the 'most played' system for our group over the past couple of years,

beating a variety of D&Ds and OSR games (even when grouped together), WFRP,

and games from the d100 family. That surprised me.

As you might have seen, I have been mulling over the

possibilities of AFF2e quite a bit lately ('capping effective SKILL', 'task resolution' and 'more task resolution'). Most of these are prompted by my thinking

that AFF2e might be a reasonable choice for a sandbox campaign, and a wish to iron out the kinks. While I am not

sure that AFF2e will beat a good ol’ B/X derived D&D variant for sheer sandbox

utility (reasons partially outlined here) with super easy NPC, monster, and

encounter generation (assign a SKILL and STAMINA score, and… well, not much more),

and with the tools for a longer term campaign in the Heroes' Companion

(holdings, hirelings, etc.), AFF2e might not be a bad choice. And, being

temporarily down to two players for the moment, and only having three or maybe

four even on a good day, I figured that a system in which starting PCs were

already pretty accomplished would fit the need of the moment.

So, yeah, AFF2e, sandbox, player freedom, blah blah blah.

And then I pluck a 'programmed adventure' – you know, a railroad – off the

shelf.

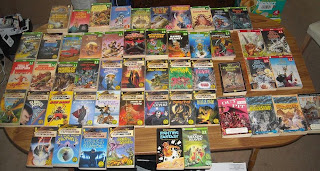

Not just any adventure, though. But the adventures in

Dungeoneer. And given that I have Blacksand! and the (pretty rare) Allansia I

have all the material for an 'adventure path' that heavily restricts player

agency. Yeah!

Nah, but surely I could subvert that, no? As the campaign

develops and as the players get a sense of the world, they will develop ideas

of their options outside the scene by scene[1] progression of the AFF campaign. Anyhow, a fortnight ago we played Tower of the Sorcerer, the introductory

adventure from Dungeoneer. And the map looks like this:

So, yes. Not much Jacquaying going on in that dungeon, but we played

it straight. And there are moments when you can really appreciate how Gascoigne

and Tamlyn were introducing new players to RPGs with this adventure. Sure,

there are few moments in which the players are able to exercise real choice,

but aside from missing that key feature of an RPG, it can serve as a useful

education.

Let me go through the 'scenes' in turn.

1. Into the Forest

The PCs are introduced to their quest as they ride through

the Darkwood Forest with Prince Barinjhar of Chalice, Morval the captain of the

Royal Guard, and a handful of soldiers. Plenty of exposition, delivered through

conversation between Barinjhar and Morval, but in truth there isn’t much for

the PCs to learn. That Xortan Throg employs Goblins, and rides a Griffon, and

sometimes his agents ride Giant Lizards, okay. But anything else? Well, there

isn’t much information needed as there aren’t many choices for the PCs to make,

so this is largely colour. Colour provided by a haughty prince and a gruff NCO.

To justify this beginning I had Grisheart – the

swashbuckling swordsman played by A – and Kumchet Wavemane – the scholarly

sorcerer played by D – having agreed to take the mission while deep in their

cups in a tavern only last night. They are working off their hangovers as they

ride, and this explains why the mission is only being explained to them as they

near Xortan Throg's tower and why they only have 11GP between them.

And the mission? Rescue Princess Sarissa of Salamonis, who

was set to marry Barinjhar. Why has Xortan Throg kidnapped her? Who knows.

2. Into the Crag

So, the PCs are given the task of sneaking into Throg's

tower through a cave in the base of the crag, which Barinjhar heads to the

front door to parlay and distract. Here, the PCs are introduced to a semblance

of dungeoneering, but in truth nothing they do matters until they arrive at a

cave. In that cave, which they must cross if they wish to progress, they will

be ambushed by Goblins. They will be. How many Goblins? Lots and lots. And what

can the PCs do? Well, according to the book, they can pointlessly roll dice

until 'each Hero has killed two or three Goblins', after which 'the rest of the

Goblins flee back into their tunnels. However, the Heroes ‘are not supposed to

die here', so you can have the Goblins flee sooner. 'It’s your film' [1], is

the advice. In other words, there is no way for the PCs to avoid this fight,

and only one permitted outcome of this fight. The players make no decisions of

consequence, and the dice that the players roll don’t matter.

I despise these types of encounters. But in this case, in

which the designers presume that this will be some players first ever encounter

with an RPG, the purpose of this encounter is to teach the players and the 'Director' the mechanics of AFF

combat.

Of course my players subverted it. A had put a point into

giving Grisheart 'Language – Goblin' at character creation, and so as the

Goblins came streaming from their tunnels he shouted, 'All hail Xortan Throg!' Well, let’s dig out the old D&D 2d6 (so perfect for AFF2e) Reaction Table and see what happens.

Confusion, a bit of time for the PCs to make their way over the cavern. And

information exchange, as Grisheart bamboozled the Goblins, who had been told to

expect adventurers, with the claim that they had come to see Xortan Throg to

help him with his adventurer problem. A few Provisions sweetened the deal,

literally.

In truth, I was always minded to allow the players to bypass

this encounter in some way, if they

came up with a reasonable plan – anything but have the players play out a scene

in which nothing that they do matters.

3. The Wizards Tower

This scene involves a number of encounters.

The PCs have to get past a portcullis trap, signposted by a

black-red bloody smear on the floor. With careful observation (no rolls - they

are looking right at the spot and asking of they see a loose flagstone) they

are able to bypass the trap by simply jumping over the trigger.

The PCs will pass two doors, behind which cower peasants,

broken men plucked from a nearby village for experimentation. Although the book

tells the Director that the PCs will hear no sound from behind these doors, I

allowed them to hear a sobbing. You have to give players some information upon

which to make a decision. They picked a lock and provided some comfort to one

of the wretches, his mind broken.

Then there is a Nightmare-esque sword trap, in which two

giant animated hands swing swords across the corridor in quick, deadly arcs. Both

Grisheart and Kumchet decided on the simplest solution, which was to use their

Dodge special skill to slip past the blades. Equal or beat 14… oh, not a

scratch.

Then there are two doors which present the players with an

interesting choice, a choice which teaches a lesson that all players should

learn. Behind these doors are the Giant Lizard and the Griffon. Now, the PCs

could probably beat the Giant Lizard (SKILL 8) in combat, or even subdue it and

use it as a mount. But the Griffon is a different prospect. SKILL 12, STAMINA

15 and with 2 Attacks, the Griffon would probably have done for Grisheart and

Kumchet. The lesson that Gascoigne and Tamlyn are trying to teach here is this; 'You don't have to open every bloody door. If it sounds and smells like there

is a big monster behind that door, and if you have been told about that big

monster earlier on, well, DON’T OPEN THE DOOR!'

And that is what my, more experienced players already knew,

and so we didn't have a TPK here.

Then there is a final trap, an illusory fireball. This took

Grisheart and Kumchet a short while to work out, but a scrap of material torn

for Kumchet’s robe was the clinching evidence.

So this scene presents a few more choices for the players to

make, and lessons that it is essential that players new to RPGs learn. They

have to reason their way past three traps, which will involve asking the

Director for more information, interacting with the environment both as players

(are there any… does it look like…) and as PCs (Kumchet tears a strip from his

robe and…). This is not just a useful lesson for fantasy RPGs in which there

are traps, but any RPG as the ‘description-question-description cycle’ of the 'information game' is often

missed by new players who treat the first description as ‘total information’

and jump straight to statements of action.

4. The Guardroom.

Another fight, this time with an indeterminate number of

Orcs and Grudthak the Ogre. Gascoigne and Tamlyn have given Grudthak some

pretty decent lines, and this should teach new Directors to give their NPCs,

even those that are most likely destined to die before the encounter is done,

some colour. And the Orcs and Ogre are also doing something as the PCs arrive –

eating a roast Goblin and gambling – which again is a good model for the new

Director to follow when the come to design their own adventures.

Grisheart and Kumchet cut down the Orcs – SKILL 5 in no time

– and Grudthak politely (well, not really, he’s insulting the PCs all the time)

waits until the PCs have finished with the Orcs and can gang up on him. He

might be SKILL 8, but he’s no match for- KCH-ZZAP! Yep, no match for a ZAP

spell causing 3d6 STAMINA damage, and so Kumchet drops to big guy just as he is

warming up.

Swigging from his Potion of Stamina (ZAP costs 4 of

Kumchet’s 12 STAMINA points), the doors on the far side of the guardroom swing

open and a voice bids the PCs 'Welcome!'

5. The Wizard’s Chamber.

Okay, so now we have Barinjhar and Xortan Throg describe

their evil plan to the PCs. Barinjhar has arranged for the disposal of Princess

Sarissa so as to avoid Chalice falling under the domination of Salamonis. Fair

enough, I guess, but he should have just killed her. The PCs have been hired to

lend credibility to Chalice’s rescue attempt. And Xortan Throg? Well, I guess

he just hates Salamonis.

Exposition over, Barinjhar leaps into the fight. At SKILL

11, he is a tough opponents, and I have given him decent armour too. Grisheart

struggles – having an effective SKILL of 9 – and Kumchet helps out with some

magic. Throg, meanwhile, sits and waits – unless a PC attacks him. When the PCs

have dealt with the prince, it becomes clear that in the finest Fighting

Fantasy traditions Throg, though exceptionally powerful, has a vulnerability.

Each time that he casts his Force Bolts at the PCs, the incense burners on either side of

his throne flare up. A and D are no mugs, and so charge at the incense burners,

dodging Force Bolts along the way. In AFF2e Force Bolts cannot be dodged, but

then who said that evil NPC magic has to work symmetrically to that used by PCs? Incense burners smashed, Grisheart and Kumchet have no problem dispatching Throg, But, whaaa-? It turns out that he was nothing more than a hollow mannequin. They rescue the princess, and to nobody's surprise, an image of

Xortan Throg appears in the fireplace to vow revenge. Job done.

Post-Credits Scene: How is Tower of the Sorcerer? Well, is linear, and there is not much player

choice. BUT, the adventure introduces

new players and Directors to both the game mechanics and the 'information game' at the heart of RPGs. It teaches

players that not every door need be opened. It shows Directors that they can

add colour even to an encounter with a handful of humanoids in a square room. And in the encounter with the 'Big Bad' it presents

both players and Directors with the idea that an encounter need not

be resolved by the PCs lucking out on the roll of the dice, whether against a high SKILL

opponent or a special skill test with negative modifiers. Indeed, resolving an encounter through dice is rather boring. But encounters can be about playing the information game then making choices that circumvent the powers of the

enemy. Or whatever is the particular hazard or obstacle. Oh, and Tower of the Sorcerer can be – quite comfortably – played in an evening, an underlooked quality in a beginning RPG adventure that will involve participants who don't know the rules and who are likely unused to sustained play.

Final Credit: Grisheart and Kumchet will return in Revenge

of the Sorcerer…

[1] AFF1e's great drawback – in my view – was its insistence

that an adventure in an RPG was like a film, with the Games Master being a 'Director'. Okay, there are a few mechanical issues too, but the 'RPG as film' conceit bleeds though into the advocated Games Mastering style, with advice to

the Director often – but certainly not always – veering close to the negation

of player agency in the pursuit of a particular 'story' outcome.